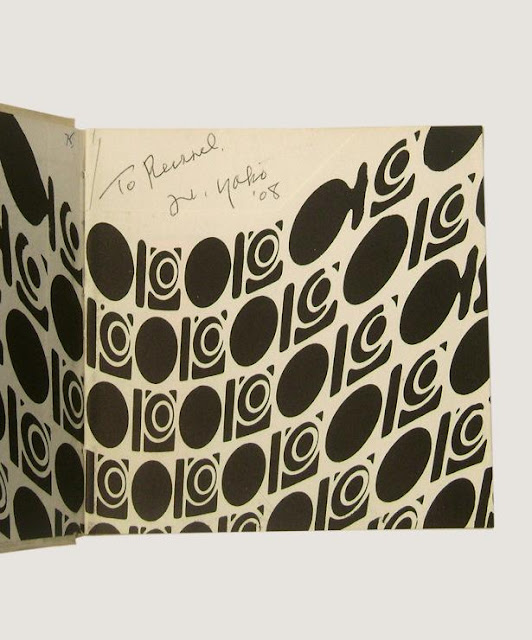

Although it might strike some as more mawkish than her provocative early efforts, Wish Tree exists on the same continuum as 1964’s Cut Piece - in which she sat stone-faced (like a modern Buddha or a proto-Abramovic) in front of an audience and asked them to snip off pieces of her clothing. When she got together with John Lennon during the latter part of the era covered by the show - the same era when she became arguably the most hated woman in the world - her art continued to engage with whatever anybody had to say about her. Drawn to words like “incomplete,” Ono has always trusted the viewer to finish her work. Here is the tricky and brilliantly fearless thing about Yoko Ono’s art: It inherently makes peace with that teenage boy’s irreverent response. (And Camille Paglia says Ono has no sense of humor!) Beginning to love Yoko Ono is a dangerous experience, because then you wonder: If Yoko Ono was something more than the woman who broke up the Beatles, then what other lies have I been told? Thanks to a slyly placed F on the cover of the accompanying catalogue, the piece is colloquially known as Museum of Modern Fart. Why is it such a perennial youthful rite of passage to misunderstand, to underestimate, even to hate Yoko Ono? What is this strange power she continues to wield? It’s as good a time as any to ask these questions, since this month she is the subject of her first official MoMA exhibit, “ Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971.” I say “official,” of course, because in 1971 Ono staged an “imaginary” MoMA exhibit, partially to protest its collection’s lack of female artists. It said: “I wish Yoko Ono hadn’t broken up the Beatles.”

I watched him pick up a pencil, scribble down his wish, and hang it on a branch of dogwood. I can remember a hell-raising boy camper - earlier in the week he’d sneaked away from the group and blown almost all of his two-week allowance on cigars - reading the placard aloud in a sarcastic tone: “When the tree is full, Yoko will collect the wishes and bury them herself at the base of the Imagine Peace Tower on Videy Island in Iceland.” He cackled. Meant to evoke the Japanese prayer trees Ono saw in her youth, these installations instruct the viewer to anonymously write down a wish on a piece of paper and hang it on the tree. One evening about ten years ago, when I was working at a summer camp in Washington, D.C., I took some kids to the Hirshhorn Museum’s sculpture garden, where one of Yoko Ono’s Wish Trees was on view. It’s a question that’s somehow echoed across cultures, continents, generations. They would, of course, see only the towering, superior Him - what could he have possibly seen in Her? She was still two years away from meeting the man with whom she would realize her dream of a completely egalitarian partnership - to symbolize this, they both wore white during their wedding ceremony - but the rest of the world wouldn’t see it that way. “They have this delicate long thing hanging outside their bodies, which goes up and down by its own will.”) The year she first staged Film Script 5, she’d already extricated herself from one failed marriage and her second was unraveling. (“I wonder why men can get serious at all,” she mused in Grapefruit. (Other variations on the piece include asking the audience not to look at any round objects in a film, or to see only red.) It was also, in its way, autobiographical: As one of the few women associated with New York’s avant-garde music scene and the “neo-Dada” Fluxus movement, Ono was by then used to being overshadowed by the more powerful and self-serious men around her. Like most of the countercultural riddles that appear in Grapefruit, Ono’s book from the same year, the instruction - titled Film Script 5 - was at once facile and mischievously impossible. In Tokyo, in 1964, the 31-year-old conceptual artist Yoko Ono organized a happening in which she screened a Hollywood film and gave the audience a simple instruction: Do not look at Rock Hudson, look only at Doris Day.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)